Number of Women in the House of Representatives

Outside observers may take the impression that women are adequately represented in the United States. From the extreme left to the extreme right, female person political leaders appear to be front end and centre in U.s.a. politics. Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin are household names all over the world. More sophisticated political observers will also know prominent congressional leaders such every bit Nancy Pelosi or Michele Bachmann. In reality, however, the United States has a big result when information technology comes to female representation. In fact, it consistently ranks lower than almost every other Western democracy in this category (Rosen Reference Rosen2011). Our own data show that, betwixt 1972 and 2012, women won less than 10 per cent of all elections contested within the US Business firm of Representatives. If race and gender are taken into business relationship together, then the representation issues of the United states are fully exposed, with black women winning only around 1.five per cent of all races contested in the aforementioned menses of time.

This commodity sheds some lite upon the underrepresentation of women in the US Congress. Nosotros contend that this underrepresentation is a issue of a rigid and static political system that grants considerable advantages to incumbent candidates. This incumbency reward constitutes a real political glass ceiling (cf. Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001) that systematically prevents women from being fairly represented. At the same time, however, nosotros likewise note that once women enter the US Congress, they do enjoy the same benefits as their male person colleagues. In brief, our terminal assessment is that in that location is no overt or covert discrimination against women within the Us Congress when it comes to their career length and service. Instead, the organisation provides a clear advantage to whomever is in power, and they currently happen to be male person. Nosotros reach this conclusion by analysing whether the careers of female Members of Congress (MCs) are whatsoever different from those of male person MCs in the US Firm of Representatives. Nosotros carefully appraise both length of service and importance of the careers of males and females, utilizing data on congressional tenure and committee assignments for all MCs elected between 1972 and 2012. With the help of descriptive and inferential statistics, nosotros discover that the length of male and female person House tenures and the importance of careers are alike for the 2 genders, with the latter mayhap even slightly favouring women.

Agreement FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN THE U.s. CONGRESS

In comparing to other Western democracies – and arguably to most countries in the world – the United States features a mix of nigh of the factors that the comparative literature identifies equally disadvantageous in terms of female representation (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2012). From a cultural point of view, the level of religious activeness, coupled with the non-existence of real leftist political movements and parties, is detrimental to the representation of women (cf. Inglehart and Norris 2003; Mateo Diaz Reference Mateo Diaz2005; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003). Socioeconomically, the gender gap in high-ranking jobs, the almost total lack of welfare provisions designed to keep women in the workforce and the high levels of income inequality mostly registered throughout the country are all factors known to contribute to low levels of female representation (cf. Darcy et al. Reference Darcy, Welch and Clark1994; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Rosenbluth et al. Reference Rosenbluth, Salmond and Thies2006). Even about of the institutional makeup of the U.s.a., from its single-fellow member balloter districts to the complete lack of gender quotas at all levels of political representation, contribute to make the United states a country that lags behind virtually other Western countries in terms of the representation of women (cf. Henig and Henig 2001; Hughes and Paxton Reference Hughes and Paxton2008; Kenny and Verge Reference Kenny and Verge2016; Krook Reference Krook2009, 2010; Matland Reference Matland1998; Paxton Reference Paxton1997; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003; Stockemer 2011). In fact, despite the fact that the percentage of women elected to state legislatures and the U.s. Congress has 'more than than quadrupled' over the past 4 decades (Cammisa and Reingold Reference Cammisa and Reingold2004: 181), women are currently withal underrepresented in United states legislatures at both federal and state levels (King Reference Rex2002). This lack of representation is especially visible at the federal level, where currently women only brand up most 18 per cent of individuals serving in Congress, even though they account for 51 per cent of the US population.

Even though the Usa Congress is 1 of the least female-friendly legislative bodies in the world, a number of women have served in it. According to Gertzog (Reference Gertzog2002), there are three distinct 'pathways' that women have pursued to enter the US Congress and, more than in general, develop political careers. In before years, the bulk of women elected to Congress were either widows of deceased MCs or women who came from families of great wealth or with well-known regional or national political connections (Foerstel and Foerstel Reference Foerstel and Foerstel1996; Kincaid Reference Kincaid1978; Solowiej and Brunell Reference Solowiej and Brunell2003). Betwixt 1966 and 1982 this moving-picture show began to change, and 58 per cent of all women elected to the Us House of Representatives could exist defined as 'strategic politicians' (Gertzog Reference Gertzog2002). Stating that female MCs are 'strategic politicians' has a number of implications in terms of candidate quality and decision to run (cf. Carson et al. Reference Carson, Engstrom and Roberts2007; Jacobson and Kernell Reference Jacobson and Kernell1983; Maestas and Rugeley Reference Maestas and Rugeley2008; Stone et al. Reference Rock, Maisel and Maestas2004). Information technology besides requires farther thought in terms of determining their objectives, given the supposition of rationality (cf. Black Reference Black1972).

On the first issue, it has been adamant that in the Us fewer women than men decide to run for public function, both in general (e.chiliad. Dominion Reference Rule1981) and in main elections (Ondercin and Welch Reference Ondercin and Welch2009). In function, this decision may be a consequence of the fact that women perceive themselves as less qualified to run for office than men do (cf. Burns et al. 2001; Deckman 2004). More interestingly, nonetheless, information technology seems that, acting strategically, women tend to run for role only when open seats are available (Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001) and their chances of winning are higher, as no candidate enjoys the incumbency advantage (cf. Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991; Cox and Katz Reference Cox and Katz1996; Gelman and King Reference Gelman and King1990; Praino and Stockemer Reference Praino and Stockemer2012a, Reference Praino and Stockemer2012b; Stockemer and Praino Reference Stockemer and Praino2012). In fact, scholars have shown that even though women in politics seem to take to piece of work harder than men in guild to reach similar outcomes (Fulton 2012), when women run for Congress they are as likely to win as their male person counterparts (Burrell Reference Burrell1994; Palmer and Simon 2005). In this context, the incumbency advantage represents a existent political glass ceiling that prevents women from inbound Congress. It works like a gendered barrier in the political opportunity structure (cf. Bjarnegård and Kenny Reference Bjarnegård and Kenny2016), and is exacerbated by the highly strategic behaviour shown by female person MCs (Carroll Reference Carroll1995; Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001).

Determining the objectives of these strategic female MCs is a slightly more nuanced job. Joseph Schlesinger's (1966) seminal piece of work on congressional ambition, besides equally other interesting enquiry on the topic (e.g. Brace 1985; Herrick and Moore 1993; Rohde 1979), posit that MCs brandish iv types of ambition: (1) discrete ambition; (2) static ambition; (3) intra-institutional ambition; and (4) progressive appetite. MCs with discrete ambition simply seek to serve their term and retire from public life. They have no involvement in running for part once again, including college office. MCs with static ambition want to create for themselves a long political career within their electric current part (Schlesinger 1966). They tend to be inactive as legislators and focus well-nigh of their attending on their constituents, in a clear effort to secure re-ballot. MCs with intra-institutional ambition aspire to leadership positions inside their electric current institution. Ordinarily, they are slap-up to get their ain legislation through and on toeing the political party line, in an effort to ultimately obtain the leadership positions they aspire to (Herrick and Moore 1993). MCs with progressive appetite desire to motility on and try to be elected to higher office (Schlesinger 1996). They are commonly very active simply quite ineffective and keep a very large staff in order to prepare their careers for the move towards a higher part (Herrick and Moore 1993). While many existing works on appetite in the U.s.a. Congress accept into account the price and/or risk of attempting ballot to higher role, the assumption that, if offered a college office without any cost or chance, every MC would take it (Rohde 1979) is virtually ubiquitous in the literature. In other words, most existing works assume that MCs accept progressive ambition (Fulton et al. 2006). Recently, Palmer and Simon (Reference Palmer and Simon2003) accept shown, even so, that female person MCs display all the types of ambition described in a higher place. They go every bit far every bit measuring singled-out characteristics of women with each category of ambition. In detail, they contend that progressive ambition is a common trait of female MCs from small states because their potential higher office constituencies coincide more with their current constituencies. They also argue that female person MCs are more likely to run for higher office when there are open seats available and when they are in their mid-careers, and then they exercise non take to sacrifice seniority. Ultimately, Palmer and Simon (Reference Palmer and Simon2003) and also Fulton et al. (2006) are suggesting that women are more strategic than men in their political appetite. Considering female person MCs are more strategic than their male counterparts, the incumbency advantage ultimately works against women as a group much more than against men (Carroll Reference Carroll1995), and the political ambition of most female MCs tends to exist mostly static or intra-institutional, as it becomes progressive only nether certain circumstances (Fulton et al. 2006; Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2003). In this context, it becomes extremely important to sympathise what happens when women manage to break this incumbency glass ceiling and get elected to Congress. In detail, whether the careers of female MCs are any unlike from the careers of male MCs is a question that remains largely unanswered.

Lawless and Theriault's (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) report on career ceilings and female retirement in the U.s.a. Congress makes a large step in this direction. It remains one of the only works explicitly focused on the issue of female service while in Congress. The authors observe that female MCs are more likely to retire than their male counterparts when they cannot achieve a position of influence (i.e. they reach a 'career ceiling'). As a consequence, Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) conclude that female MCs enjoy shorter careers than males. Their work is based on Theriault's (Reference Theriault1998) idea that MCs who achieve a 'career ceiling' are more likely to retire than newly elected MCs or powerful long-serving MCs. In more detail, they observe that, once seniority is accounted for, male and female MCs are equally likely to face career ceilings, but female MCs are more likely to retire and get out politics altogether, once they hit such career ceilings (Lawless and Theriault Reference Lawless and Theriault2005). To a certain degree, their unabridged argument hinges on the thought that 'reaching a career ceiling is more dramatic for women than men considering of gender differences motivating the conclusion to run for Congress' (Lawless and Theriault Reference Lawless and Theriault2005: 585). Their interpretation of such differences in motivation is loosely based on Bledsoe and Herring's (1990) well-known argument that ambition is a masculine characteristic (see Ruble Reference Ruble1983) that directly and significantly determines the behaviour of men, but not that of women. As in most existing works (east.k. Fulton et al. 2006), political ambition here is implicitly divers in terms of progressive ambition. Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) demonstrate that both men and women often attain career ceilings, but while males either tend to stick around considering they get satisfaction from merely serving in Congress, or determine to run for higher role because of their (progressive) appetite (cf. Fox Reference Trick1997), women usually adopt to retire. Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) conclude and so that female MCs volition have shorter careers than male person MCs. Instead, what they actually notice is that female MCs have lower progressive ambition than male person MCs. The 'shorter career' conclusion remains an untested and unexplored hypothesis.

VARIABLES AND DATA

We guess congressional careers by how long men and women stay in Congress and whether or not they get nominated to important committees, utilizing ii indicators as dependent variables. The first indicator is the number of years somebody stays in office. Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) take demonstrated that role tenure is not just an indication of a successful career, but also provides MCs with distinct powers, such every bit more than influence in drafting legislation and influencing policy. The second indicator is the congressional committee that individual MCs bring together, as important committees assist MCs attain their career goals (Grimmer and Powell 2013).

Committee assignments are the result of a long and complicated interaction between private preferences of MCs and preferences of the parties and party leaders who control the assignments (Leighton and Lopez 2002). Ultimately, still, recent scholarship shows that not only does the will of the party prevail, merely besides most fellow member preferences are actually not accommodated past the parties (Frisch and Kelly Reference Frisch and Kelly2004). When it comes to female MCs, this relationship becomes reversed over successive terms, at least for Autonomous women (Frisch and Kelly Reference Frisch and Kelly2003). One time an MC is function of a committee, she starts to accumulate seniority, and the more than seniority an incumbent MC accumulates, the more likely information technology is that she volition retain a committee assignment, even in the presence of substantial electoral loss by her political party (Grimmer and Powell 2013). In other words, MCs who are able to exploit the incumbency reward and win multiple elections are often likely to reach and maintain a committee assignment that suits their appetite.

Abramowitz (Reference Abramowitz1991) refers to a number of committeesFootnote 1 as 're-election committees'. These committees provide their members with electoral and non-balloter advantages, including a college likelihood of obtaining federal projects within their districts and the possibility of linking the economic involvement of the commission to the deliberation of the commission itself (Bullock Reference Bullock1976). In other words, they provide their members with name recognition also as pork and patronage to distribute, among other things. Re-election committees can be valuable to MCs with unlike types of ambition as they are perceived as assisting with re-election.

Co-ordinate to Smith and Deering'due south (1997) classification of congressional committees, the near influential committees in the US Firm of Representatives are Appropriations, Budget, Rules, and Ways and Means. These four committees are known as 'prestige committees'. They affect every member of the House and provide their members influence and prestige that become beyond serving constituents or pursuing personal policy interests (Smith and Deering 1997). MCs with intra-institutional ambition and MCs with progressive ambition volition be particularly interested in serving in these committees, the erstwhile in order to solidify their power within their party, the latter in order to apply their prominence in their pursuit of higher office.

We include in our analysis both membership in re-election committees and membership in prestige committees.Footnote ii Nosotros compiled data for these indicators for all US House of Representatives elections held betwixt 1972 and 2012, utilizing data from the clerk of the U.s. House of Representatives and some data shared with us by other scholars.Footnote three

Our contained variable of interest is the dichotomous variable Female MCs, coded 1 for all female person MCs who were successfully elected, 0 otherwise. Equally gender is non the only variable that influences political careers, we besides include in our assay boosted relevant covariates.

Personal Characteristics

Age at First Ballot is the historic period of successful candidates at the time of ballot. In line with previous research (e.m. Brace Reference Brace1985; Frantzich 1978; Moore and Hibbing Reference Moore and Hibbing1992), nosotros believe that politicians who are elected at a relatively immature age (between 30 and twoscore) have sufficient time to advance in their congressional careers. Moreover, older freshmen MCs also seem unlikely candidates to be nominated to important committees. Education is an ordinal variable coded 1 for MCs with high schoolhouse pedagogy or lower, two for MCs with a bachelor'southward caste, 3 for MCs belongings master's degrees, and four for all MCs in possession of a doctorate. Nosotros presume that MCs with higher levels of education (cf. Docherty Reference Docherty2005; Studlar et al. Reference Studlar, Alexander, Cohen, Ashley, Ferrence and Pollard2000) have the necessary qualifications for a long and successful congressional career. Finally, Republican MCs is a dichotomous variable coded 1 for all Republican MCs, and 0 otherwise. It controls for differences in political party affiliation, equally they be in terms of both committee assignment (Frisch and Kelly Reference Frisch and Kelly2003) and career length (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones1997).

Electoral Controls

Personal Advantage is the margin of vote obtained past each candidate at the previous ballot. Information technology accounts for the personal electoral forcefulness of individual MCs (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991). The covariates Incumbent Expenditures, Challenger Expenditures and their respective squares are the total dollar amount of the electoral expenses of elected MCs and their opponents and the same value squared, to control for the non-linear relationship between campaign expenditure and electoral success (cf. Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991; Jacobson Reference Jacobson1978, Reference Jacobson1990). The variable Opponent Score is an ordinal variable coded 1 for opponents who never held elective office, two for opponents who held elective offices, 3 for opponents who were state legislators in the by, and 4 for opponents who were former members of the US House of Representatives. It is directly based on Jacobson'due south (Reference Jacobson1989) challenger scores that rank the 'quality' of individuals running against incumbents based on their political experience and the understanding that more than formidable opponents may attract more votes, therefore diminishing the magnitude of the electoral success of incumbents, which, in turn, is likely to influence MCs' careers in Congress. The variable Scandal Accusation is a dichotomous variable coded 1 for MCs field of study to an investigation by the US Firm Ideals Committee, 0 otherwise. It accounts for the fact that several contempo studies (e.g. Basinger Reference Basinger2013; Praino et al. Reference Praino, Stockemer and Moscardelli2013) have establish that scandals have a high likelihood of catastrophe an MC's congressional career. District Partisanship is the district-level margin of victory/defeat of the nigh contempo presidential candidate belonging to the same party of the successful candidate at each district. It has been utilized by a plethora of studies based on the US Congress (east.thousand. Ansolabehere et al. Reference Ansolabehere, Snyder and Stewart2001) as a good proxy of the underlying ideological/partisan tendencies of each congressional district. Our variable Adapted ADA Distance gauges the distance between the score associated with the almost ideologically extreme member of the political political party of successful candidates and their own ADA score,Footnote iv as adjusted by Anderson and Habel (Reference Anderson and Habel2009). Being a measure out of conformity to the overall voting of each private MC to the votes of other members of their own political party, this variable controls for political party loyalty, which has been identified by scholars as an important determinant of both commission assignment (Lee Reference Lee2008; Leighton and Lopez 2002) and length of political career (Theriault Reference Theriault1998). Finally, we create a dummy variable called Region South coded 1 for all states in the Southern RegionFootnote five of the United states of america and 0 otherwise, in order to business relationship for the particularities of the American South.

Institutional Appetite Controls

Leadership positions within the legislative political parties and/or inside the US Congress in general (east.m. committee chairmanships or minority party ranking within such committees) are sought by MCs as they progress in their political careers, according to the specific type of ambition they display (cf. Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). Political parties have the virtually power in determining private MCs' assignments to committees, and such power increases when their political party is in the majority (Heberlig and Larson Reference Heberlig and Larson2012). In essence, it is reasonable to expect that if an MC holds a leadership position or a prestigious appointment, she will have a large incentive to continue her career (Hall and Houweling 1995). Therefore, we computed a number of dichotomous covariates that take these factors into account. Leadership Position is coded i for all MCs who concur a leadership position either inside the party or within the House Committee structure.Footnote six Majority Party Leaders and Minority Political party Leaders are coded 1 for all MCs who serve in the Congressional party leadership (i.eastward. the speaker of the House and the bulk/minority leaders and whips). Finally, Bulk Party MCs is coded i for all MCs who vest to the bulk party in the Business firm at each relevant point in time.

Interaction Terms

In order to appraise whether gender plays a direct role in determining the length and importance of the political careers of MCs or moderates the issue of other variables, we also compute a number of variables past interacting our gender variable with other dichotomous variables. These interactions are fundamental in gild to rule out the possibility of gendered effects within the relationships we describe.

METHOD

We test the hypothesis that female MCs enjoy shorter careers than male MCs by employing a iii-step process. First, nosotros descriptively analyse the average number of years each of the two genders has spent in Congress. Second, we run a Kaplan–Meier examination to see if the probability of survival is unlike for the two genders. Third, we estimate an event history model to measure the duration in years until the end of an MC's tenure.Footnote 7 Effect history analysis has proved to be an appropriate technique for studying leadership duration (cf. Ferris and Voia Reference Ferris and Voia2009; Kerby Reference Kerby2011). In detail, this technique allows us to measure the influence of an MC'south gender and her personal and circumstantial characteristics on the fourth dimension it takes her to go out her elected office. Because we are measuring the duration that each MC stays in Congress, we average all independent variables over this time catamenia.Footnote 8

Nosotros also appoint in a three-pace procedure, repeating each step for both assignment to re-ballot committees and consignment to prestige committees, in lodge to examination the hypothesis that male and female MCs have different careers within the Us House. First, we measure the total number of individuals who have served in these types of committees from 1972 to 2012. Second, we calculate and analyse the percentage of men and women who served in one of these committees. Tertiary, nosotros estimate two split time-series logistic regressions to determine whether at that place is a difference in the two genders' likelihood of being nominated to either a re-ballot committee or a prestige committee.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In our data set, ane,818 individuals accept served in the US Congress, with 1,623 being men and 195 women. Men, on average, seem to stay longer in the Business firm than women, with an average tenure of slightly more than 10 years (v terms), against an average of seven.8 years (less than 4 terms) for women. An contained samples t-test confirms that this deviation in tenure is statistically meaning (t=4.07, p=0.000). Hence, at outset glance, our results indicate that there is, in fact, a bias toward longer careers in favour of men in the United states of america Congress (run across Table 1).

Tabular array i Descriptive Statistics Measuring Average Tenure of Male and Female person House Members

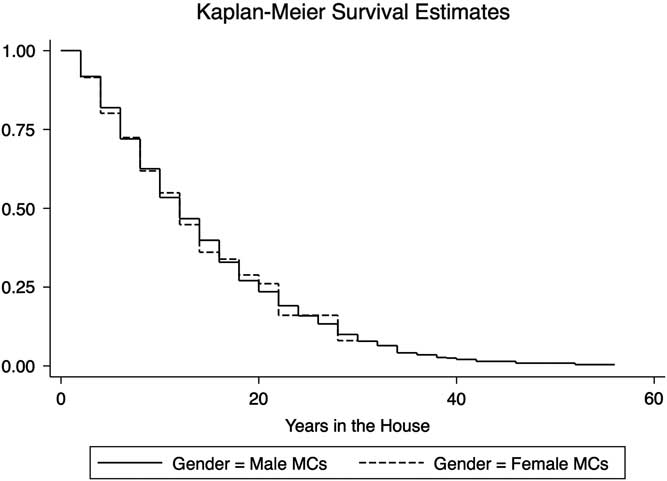

Our Kaplan–Meier estimation, even so, does not confirm this finding. Comparison the line displaying the survival rate of women with the line showing the survival rate of men, we see that up to about 30 years there are no differences between the 2 genders pertaining to their likelihood of staying in office. Rather, the differences between the two genders just become pronounced after 30 years. While up to 2012 the longest any woman had served in the United states of america House was 30 years, there were almost 100 men who had served 30 or more years. By right censoring our information, the Kaplan–Meier estimation accounts for the fact that women accept only recently joined Congress in larger numbers and hence cannot take the same long careers men have enjoyed (see Effigy 1).

Figure i The Survival of Males and Females in the US House of Representatives

In fact, men with long congressional careers drive the descriptive statistics and the means examination by giving men an edge. The corresponding log rank exam also confirms that the two curves are not statistically different from one another (χii=1.12, p=0.28). Hence the seemingly positive human relationship betwixt male gender and longer careers is an artefact of the information and of the fact that women take but entered the House in larger numbers relatively recently. For example, effectually 40 per cent of the women who served in the House betwixt 1972 and 2012 had non finished their tenure and were even so serving at that place in 2012. If we compare this high percentage to the meagre twenty per cent of men whose congressional careers had not come up to an end in 2012, it is likely that in 10 or 20 years, there will be women with a House tenure of 35 or xl years, likewise.

Table ii confirms the Kaplan–Meier estimation. Our dummy variable for female person MC is not statistically significant. The positive sign of the coefficient implies that existence female increases an MC's chances of get outFootnote nine compared with her male colleagues. However, the coefficient is not statistically significant and too small to brand whatever meaningful difference.

Table ii The Event History Model Measuring the Influence of Gender on Business firm Members' Tenure

All the statistically pregnant control variables have the expected sign: MCs who tend to receive large electoral margins and spend big amounts of coin during campaigns are less likely to leave the US Business firm; MCs who tend to face more formidable opponents who spend big amounts of money, every bit well as MCs kickoff elected at an older age, take a college probability of leaving the US House. Our institutional controls bear witness that MCs in leadership positions, every bit well as those who serve in prestige committees, are less likely to see their House careers ended. They as well show that MCs serving in re-election committees are more likely to get out the House.Footnote 10 None of the interaction terms we included in the model is statistically significant, suggesting that at that place are no gendered differences in the relationships discussed higher up betwixt career length and political party leadership status, service in important committees, or party amalgamation.

Tabular array 3 illustrates that 61 per cent of all men in our sample at i point or some other of their career managed to get assigned to a re-election commission, while 31 per cent served in a prestige committee. It also shows, however, that 57 per cent of all women managed to be part of a re-ballot commission, and 31 per cent served in a prestige committee. In cursory, the descriptive data bear witness that there is no deviation in assignment to prestige committees betwixt male and female MCs, while men announced to have a pocket-sized edge over women within re-election committees. Notwithstanding, two independent samples t-tests (t=0.05, p=0.96; and t=0.91, p=0.36, respectively) bear witness that there is no statistically relevant difference in either example.

Table 3 Descriptive Statistics Measuring Re-Election Committee Assignments of Male and Female Business firm Members

Table four provides some additional information on these data. In fact, Table 4 gathers the percentage of all male and female MCs who became function of a re-election commission or of a prestige committee afterward each election included in our assay. The percentage of female person MCs serving in one of these highly desirable committees generally increases throughout the years. More than interestingly, the table shows that in most election years the percentage of female MCs serving in 1 of these types of committees is at to the lowest degree comparable to the pct of male MCs obtaining the same desirable assignment.

Table 4 Pct of All Males and Females Serving in Congressional Committees, 1972–2012

Conspicuously, our descriptive data do not present any evidence in support of any kind of female person disadvantage in terms of assignment to of import congressional committees. On the contrary, it may exist pointing in the contrary direction, especially for more recent years, with women having an reward in relation to their male colleagues. Our multivariate analysis somewhat confirms this picture (see Table five). In the two models, our independent variable of involvement Female MC indicates that, overall, women are just as likely as menFootnote 11 to serve in a re-ballot or a prestige committee.

Tabular array 5 Fourth dimension-Series Logistic Regression of Assignment to Congressional Committees

A probability transformation of the results of our logistic regression helps to put our findings in perspective. In fact, keeping all other variables at their mean – and setting all dichotomous controls to 0 – our model predicts that the probability that a female person serves in a re-election committee stands at effectually 17 per cent, while the probability that a male person serves in the aforementioned type of committee is just 8 per cent. On the contrary, the probability of a female serving in a prestige commission is 13 per cent, while that of a male serving in the same blazon of committee stands at xv per cent. In other words, our model is predicting that women have a slight advantage when information technology comes to serving in re-election committees and essentially exactly the same likelihood as their male colleagues of serving in prestige committees.

Our logistic regressions also betoken that MCs with a history of larger balloter margins are less likely to be assigned to re-election committees but more probable to end up in prestige committees, which appears to be an indication that those with high balloter margins practise not demand an consignment to a re-election committee and tin dedicate fourth dimension to consolidate their ability and influence within the Firm (cf. Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991; Smith and Deering 1997). This finding, in particular, provides some context to the finding presented to a higher place that MCs serving in re-election committees tend to have shorter careers than other MCs. Our results also show that the larger the ideological distance betwixt MCs and the most ideologically extreme fellow member of their party, the more likely they are to serve in a re-election committee, simply the less probable they volition be to serve in a prestige committee. Finally, MCs with higher levels of education seem to be less likely to serve in re-election committees.

Our institutional ambition controls show that MCs affiliated with the majority party are less probable to serve in re-election committees, while both bulk and minority party leaders are less likely to serve in prestige committees. In conclusion, our interactions testify that there are no gendered differences between party lines in terms of consignment to of import committees.

Overall, information technology seems that women not merely accept equal chances of winning balloter races (cf. Dolan Reference Dolan2008), but also take very similar political careers in the US Business firm to those of their male person colleagues. In fact, between 1972 and 2012, our data prove that 28 per cent of all men who served in the House and 34 per cent of all women never served in either an electoral or a prestige committee. In other words, around xxx per cent of male and female MCs reached some sort of 'career ceiling' within the House. Statistically, this difference is negligible, as confirmed by an independent samples t-examination (t=1.seven, p=0.09). In addition, the opposite is also true. Around xx per cent of all males who serve in the House during the same fourth dimension period and 22 per cent of females served throughout their careers in both a re-election and a prestige committee. One time again, such a difference is not statistically relevant (t=0.8, p=0.iv). In other words, almost identical percentages of males and females substantially seem to attain very piddling while in the House, while identical numbers of both genders manage to rise to the virtually prestigious, advantageous and influential positions. Overall, female MCs and male MCs appear to have extremely similar careers within the U.s.a. House of Representatives.

CONCLUSION

The consequence of female representation in national legislative bodies is not but symbolic, it is besides noun (see Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). Existing scholarship (e.g. Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2001; Celis Reference Celis2009) has clearly shown that the presence of women in prestigious political positions increases the chance that policy debates and bills discussed focus on issues of importance to women. Consequently, meaningful gender equality can just be achieved if women occupy relevant policy positions within a given political system (cf. Swers Reference Swers2001). Mutatis mutandis, an underrepresentation of women is likely to create a lack of focus on women's problems, policy preferences and concerns within the legislative process, thus creating a 'gender gap' in policymaking. In the previous pages, nosotros show that men and women take similar political careers in the US House of Representatives in terms of both length of service and importance of their careers. In this light, female underrepresentation appears to be the consequence of a rigid and static political organization that has created an incumbency glass ceiling (cf. Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001) that, together with other social forces, constitutes a gendered institutional bulwark (cf. Bjarnegård and Kenny Reference Bjarnegård and Kenny2016) that prevents women from being elected to the US Congress. While our research ultimately posits that once women do go elected to Congress they then start to savour the protection of the same glass ceiling that was preventing them entering Congress, this does not mean that women are inevitably going to become adequately represented in the US Congress. In fact, the other social forces we mention (e.m. the fact that women are more strategic than men and feature unlike types of appetite) may keep to ensure that American women remain disadvantaged in politics in comparison to women in other countries. In fact, while our research rules out the beingness of overt or covert gender discrimination inside the US Congress when it comes to the career length and service of the two genders, it does not offer whatever insight on why, how and how many women consider running for Congress or public office in general. Knowing that when women become elected their careers are as lengthy and every bit successful as the careers of men is a expert starting time. Nevertheless, much more than work is needed in order to understand how to bring female representation in the Usa to the same level equally other developed countries.

References

Abramowitz, A.I. (1991), 'Incumbency, Campaign Spending, and the Decline of Competition in the U.S. House Elections', Journal of Politics, 53(ane): 34–56.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Anderson, Due south. and Habel, P. (2009), 'Revisiting Adjusted ADA Scores for the U.S. Congress, 1947–2007', Political Analysis, 17(1): 83–88.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Ansolabehere, S. , Snyder, J.G. and Stewart, C. (2001), 'Candidate Positioning in U.S. Firm Elections', American Journal of Political Science, 45(1): 136–159.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Arceneaux, M. (2001), 'The "Gender Gap" in State Legislative Representation: New Data to Tackle an Quondam Question', Political Enquiry Quarterly, 54(i): 143–160.Google Scholar

Basinger, S.J. (2013), 'Scandals and Congressional Elections in the Post-Watergate Era', Political Research Quarterly, 66(2): 385–398.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Bjarnegård, E. and Kenny, M. (2016), 'Comparing Candidate Selection: A Feminist Institutionalist Approach', Government and Opposition, 51(3): 370–392.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Black, Grand.S. (1972), 'A Theory of Political Ambition: Career Choices and the Part of Structural Incentives', American Political Science Review, 66(1): 144–159.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Bledsoe, T. and Herring, M. (1990), 'Victims of Circumstances: Women in Pursuit of Political Role', American Political Science Review, 84(1): 213–223.Google Scholar

Box-Steffensmeier, J.Grand. and Jones, B.S. (1997), 'Event History Models in Political Science', American Journal of Political Scientific discipline, 41(4): 1414–1461.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Box-Steffensmeier, J.M. and Jones, B.Southward. (2004), Event History Modeling: A Guide for Social Scientists (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Brace, P. (1985), 'A Probabilistic Arroyo to Retirement from the U.S. Congress', Legislative Studies Quarterly, 10(1): 107–123.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Bullock, C.Southward. (1976), 'Motivations for U.S. Congressional Committee Preferences: Freshmen of the 92nd Congress', Legislative Studies Quarterly, 1(ii): 201–212.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Burns, N. , Schlozman, K.L. and Verba, Southward. (2001), The Individual Roots of Public Action (New Haven: Harvard University Press).Google Scholar

Burrell, B. (1994), A Woman's Place in the House: Campaigning for Congress in the Feminist Era (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Printing).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Cammisa, A.M. and Reingold, B. (2004), 'Women in State Legislatures and State Legislative Research: Beyond Sameness and Difference', State Politics and Policy Quarterly, four(two): 181–210.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Carroll, S.J. (1995), Women every bit Candidates in American Politics (Bloomington: Indiana University Printing).Google Scholar

Carson, J.50. , Engstrom, East.J. and Roberts, J.G. (2007), 'Candidate Quality, the Personal Vote, and the Incumbency Advantage in Congress', American Political Science Review, 101(2): 289–301.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Celis, M. (2009), 'Substantive Representation of Women (and Improving Information technology): What Information technology Is and Should Exist About?', Comparative European Politics, 7(1): 95–113.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Cox, G.West. and Katz, J.Due north. (1996), 'Why Did the Incumbency in U.S. Elections Grow?', American Periodical of Political Science, 40(ii): 478–497.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Cox, G.W. and McCubbins, Chiliad.D. (2005), Setting the Calendar: Responsible Party Government in the US House of Representatives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Darcy, R. , Welch, S. and Clark, J. (1994), Women, Elections, and Representation (Lincoln: Nebraska Academy Press).Google Scholar

Deckman, M. (2004), 'Women Running Locally: How Gender Affects Schoolhouse Board Elections', Political Science and Politics, 37(one): 61–62.Google Scholar

Docherty, D.C. (2005), Legislatures (Vancouver: UBC Printing).Google Scholar

Dolan, G. (2008), 'Is There a "Gender Affinity Effect" in American Politics?', Political Research Quarterly, 61(i): 79–89.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Ferris, J.S. and Voia, K. (2009), 'What Determines the Length of a Typical Canadian Parliamentary Authorities?', Canadian Periodical of Political Science, 42(four): 881–910.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Foerstel, K. and Foerstel, H.N. (1996), Climbing the Loma: Gender Conflict in Congress (Westport, CT: Praeger).Google Scholar

Frantzich, S.Due east. (1978), 'Opting Out: Retirement from Business firm of Representatives, 1968–1974', American Politics Quarterly, six(3): 251–273.Google Scholar

Frisch, Due south.A. and Kelly, S.Q. (2003), 'A Place at the Table: Women'southward Committee Requests and Women's Commission Assignments in the U.Southward. House', Women and Politics, 25(3): 1–26.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Frisch, S.A. and Kelly, S.Q. (2004), 'Cocky-Pick Reconsidered: Business firm Committee Consignment Requests and Constituency Characteristics', Political Research Quarterly, 57(2): 325–326.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Fulton, S.A. (2012), 'Running Backwards and in High Heels: The Gendered Quality Gap and Incumbent Balloter Success', Political Research Quarterly, 65(two): 303–314.Google Scholar

Fulton, S.A. , Maestas, C.D., Maisel, L.S. and Rock, Due west.J. (2006), 'The Sense of a Woman: Gender, Ambition, and the Conclusion to Run for Congress', Political Enquiry Quarterly, 59(ii): 235–248.Google Scholar

Gelman, A. and King, Thou. (1990), 'Estimating Incumbency Advantage without Bias', American Journal of Political Scientific discipline, 34(four): 1142–1164.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Gertzog, I.N. (2002), 'Women's Irresolute Pathways to the U.Southward. House of Representatives: Widows, Elites, and Strategic Politicians', in C. S. Rosenthal (ed.), Women Transforming Congress (Norman: University of Oklahoma Printing): 95–118.Google Scholar

Grimmer, J. and Powell, E.N. (2013), 'Congressmen in Exile: The Politics and Consequences of Involuntary Committee Removal', Journal of Politics, 75(4): 907–920.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Hall, R.L. and van Houweling, R.P. (1995), 'Avarice and Appetite in Congress: Representatives' Decisions to Run or Retire from the U.S. House', American Political Science Review, 89(1): 121–136.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Heberlig, E.S. and Larson, B.A. (2012), Congressional Parties, Institutional Appetite, and the Financing of Majority Control (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Henig, R. and Henig, S. (2001), Women and Political Power (New York: Routledge).Google Scholar

Herrick, R. and Moore, K.K. (1993), 'Political Appetite's Outcome on Legislative Behavior: Schlesinger's Typology Reconsidered and Revised', Journal of Politics, 55(three): 765–776.Google Scholar

Hughes, Chiliad.M. and Paxton, P. (2008), 'Continuous Change, Episodes, and Critical Periods: A Framework for Understanding Women's Political Representation over Time', Politics and Gender, iv(2): 233–264.Google Scholar

Inglehart, R. and Norris, P. (2003), Rise Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Alter effectually the World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).Google Scholar

Jacobson, G.C. (1978), 'The Furnishings of Campaign Spending in Congressional Elections', American Political Science Review, 72(ii): 469–491.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Jacobson, G.C. (1989), 'Strategic Politicians and the Dynamics of U.S. House Elections, 1946–86', American Political Science Review, 83(three): 773–793.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Jacobson, G.C. (1990), 'The Effects of Entrada Spending in House Elections: New Evidence for Old Arguments', American Journal of Political Science, 34(two): 334–362.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Jacobson, 1000.C. and Kernell, Due south. (1983), Strategy and Choice in Congressional Elections (New Haven: Yale University Printing).Google Scholar

Kenny, M. and Verge, T. (2016), 'Opening up the Black Box: Gender and Candidate Selection in a New Era', Government and Opposition, 51(3): 351–359.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Kerby, M. (2011), 'Combining the Hazards of Ministerial Appointment and Ministerial Leave in the Canadian Federal Cabinets', Canadian Periodical of Political Science, 44(3): 595–611.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Kincaid, D.D. (1978), 'Over his Dead Body: A Positive Perspective on Widows in the U.s.a. Congress', Political Research Quarterly, 31(ane): 96–104.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Rex, J.D. (2002), 'Single-Member Districts and the Representation of Women in American State Legislatures: The Effects of Balloter System Change', State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 2(2): 161–175.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Krook, Thou.L. (2009), Quotas for Women in Politics: Gender and Candidate Option Reform Worldwide (New York: Oxford University Press).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Krook, Yard.L. and Pearson, K. (2010), Quotas for Women in Politics: Gender and Candidate Selection Reform Worldwide (Oxford: Oxford University Press).Google Scholar

Lawless, J.L. and Theriault, S.M. (2005), 'Will she Stay or Will she Go? Career Ceilings and Women'southward Retirement from the U.S. Congress', Legislative Studies Quarterly, xxx(iv): 581–596.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Lee, D.J. (2008), 'Going Once, Going Twice, Sold! The Commission Assignment Process as an All-Pay Auction', Public Choice, 135(3): 237–255.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Leighton, Westward.A. and Lopez, E.J. (2002), 'Commission Assignments and the Cost of Political party Loyalty', Political Enquiry Quarterly, 55(1): 59–90.Google Scholar

Maestas, C.D. and Rugeley, C.R. (2008), 'Assessing the "Experience Bonus" through Examining Strategic Entry, Candidate Quality, and Entrada Receipts in U.S. House Elections', American Journal of Political Science, 52(iii): 520–535.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Mateo Diaz, M. (2005), Representing Women? Female person Legislators in West European Parliaments (Colchester: ECPR Press).Google Scholar

Matland, R.E. (1998), 'Women's Representation in National Legislatures; Developed and Developing Countries', Legislative Studies Quarterly, 23(1): 107–129.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Moore, One thousand.K. and Hibbing, J.R. (1992), 'Is Serving in Congress Fun Again? Voluntary Retirements from the House since the 1970s', American Periodical of Political Science, 36(3): 824–828.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Norris, P. (2004), Electoral Technology: Voting Rules and Political Beliefs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Norris, P. (2006), 'The Impact of Balloter Reform on Women'south Representation', Acta Politica, 41(2): 197–213.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Ondercin, H.L. and Welch, Southward. (2009), 'Comparison Predictors of Women's Congressional Ballot Success: Candidates, Primaries, and the Full general Ballot', American Politics Research, 37(iv): 593–613.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Palmer, B. and Simon, D. (2001), 'The Political Glass Ceiling: Gender, Strategy, and Incumbency in U.S. Firm Elections, 1978–1998', Women and Politics, 23(1): 59–78.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Palmer, B. and Simon, D. (2003), 'Political Appetite and Women in the U.South. House of Representatives, 1916–2000', Political Research Quarterly, 56(2): 127–138.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Palmer, B. and Simon, D.M. (2005), 'When Women Run against Women: The Hidden Influence of Female Incumbents in Elections to the Usa House of Representatives, 1956–2002', Politics and Genderr, 1(1): 39–63.Google Scholar

Paxton, P. (1997), 'Women in National Legislatures: A Cantankerous-National Analysis', Social Science Inquiry, 26(iv): 442–464.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Paxton, P. and Kunovich, Due south. (2003), 'Women's Political Representation: The Importance of Ideology', Social Forces, 82(ane): 87–114.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Pitkin, H.F. (1967), The Concept of Representation (Berkeley: University of California Press).Google Scholar

Praino, R. and Stockemer, D. (2012a), 'Tempus Fugit, Incumbency Stays: Measuring the Incumbency Advantage in the U.S. Senate', Congress and the Presidency, 39(2): 160–176.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Praino, R. and Stockemer, D. (2012b), 'Tempus Edax Rerum: Measuring the Incumbency Advantage in the U.Due south. House of Representatives', Social Science Journal, 49(iii): 270–274.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Praino, R. , Stockemer, D. and Moscardelli, Five.K. (2013), 'The Lingering Effect of Scandals in Congressional Elections: Incumbents, Challengers, and Voters', Social Science Quarterly, 94(4): 1045–1061.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Reynolds, A. (1999), 'Women in the Legislatures and Executives of the World: Knocking at the Highest Drinking glass Ceiling', World Politics, 51(4): 547–572.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Rohde, D.W. (1979), 'Chance-begetting and Progressive Appetite: The Case of Members of the United States House of Representatives', American Journal of Political Science, 23: 1–26.Google Scholar

Rosen, J. (2011), 'The Effects of Political Institutions on Women'south Political Representation: A Comparative Analysis of 168 Countries from 1992 to 2010', Political Research Quarterly, 66(ii): 306–321.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Rosenbluth, F. , Salmond, R. and Thies, K.F. (2006), 'Welfare Works: Explaining Female Legislative Representation', Politics and Gender, 2(two): 165–192.Google Scholar

Ruble, T.50. (1983), 'Sex Stereotypes: Issues of Change in the 1970s', Sex Roles, 9(3): 397–402.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Rule, W. (1981), 'Why Women Don't Run: The Disquisitional Contextual Factors in Women's Legislative Recruitment', Political Enquiry Quarterly, 34(i): 60–77.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Schlesinger, J.A. (1966), Appetite and Politics: Political Careers in the United States (Chicago: Rand McNally).Google Scholar

Solowiej, L. and Brunell, T.Fifty. (2003), 'The Archway of Women to the Us Congress: The Widow Effect', Political Research Quarterly, 56(three): 283–292.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Stockemer, D. (2011), 'Women's Parliamentary Representation in Africa: The Bear on of Democracy and Corruption on the Number of Female Deputies in National Parliaments', Political Studies, 59(3): 693–712.Google Scholar

Stockemer, D. and Praino, R. (2012), 'The Incumbency Advantage in the US Congress: A Roller-Coaster Relationship', Politics, 32(3): 220–230.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Stone, W.J. , Maisel, S.L. and Maestas, C.D. (2004), 'Quality Counts: Extending the Strategic Politican Model of Incumbent Deterrence', American Journal of Political Science, 48(3): 479–495.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Studlar, D.T. , Alexander, D.50. , Cohen, J.East. , Ashley, M.J. , Ferrence, R.Thousand. and Pollard, J.S. (2000), 'A Social and Political Profile of Canadian Legislators, 1996', Journal of Legislative Studies, 6(two): 93–103.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Swers, M. (2001), 'Understanding the Policy Impact of Electing Women: Prove from Research on Congress and Country Legislatures', Political Science and Politics, 34(2): 217–220.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Theriault, South.One thousand. (1998), 'Moving Upwards or Moving Out: Career Ceilings and Congressional Retirement', Legislative Studies Quarterly, 23(3): 419–433.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Tremblay, M. (2012), 'Les femmes et les partis politiques au Québec: de l'exclusion à une inclusion inachevée', in R. Pelletier (ed.), Les partis politiques québécois dans la tourmente. Mieux comprendre et évaluer leur rôle (Québec: Presses de 50'Université Laval): 69–108.Google Scholar

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/government-and-opposition/article/career-length-and-service-of-female-policymakers-in-the-us-house-of-representatives/EAD3C8225961D262D71091FBEF0DD9CE

0 Response to "Number of Women in the House of Representatives"

Postar um comentário